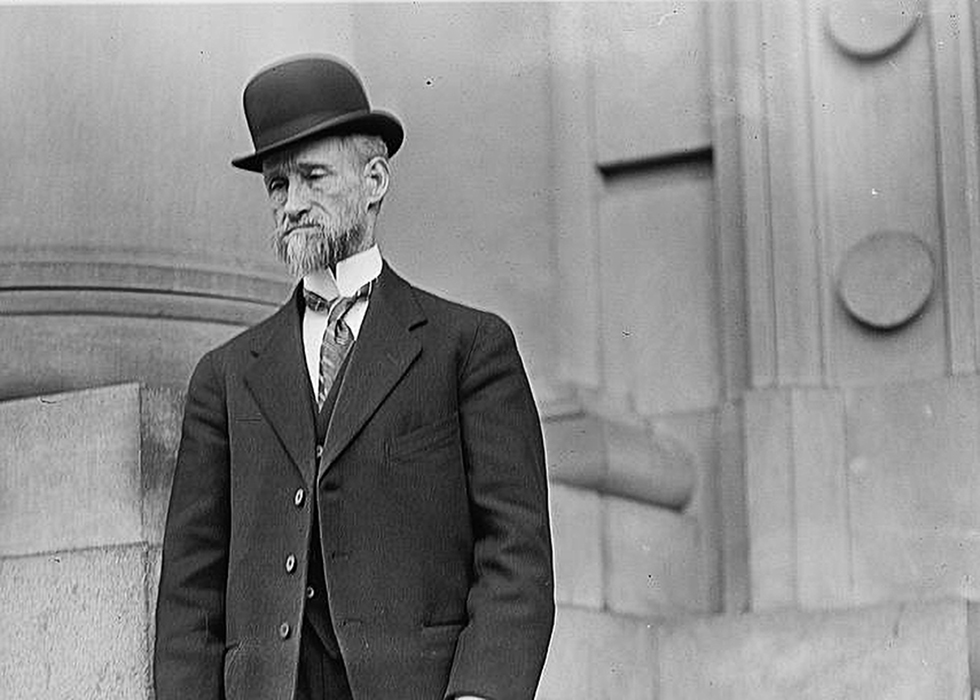

Resident Spotlight: Major Charles Hubner, Poet Laureate of the South

Charles Hubner was born on January 16, 1835 in Baltimore, to Bavarian parents. His mother was a teacher and his father a merchant tailor. They lived comfortably, with Charles studying literature and music, his two great loves. In fact, at age 10 Charles wrote his first hymn, a sign of things to come for him.

His route to art school took him past a hospital, where, one day, a plain coffin was being taken to a hearse nearby. Two gentlemen had their hats off, standing by with respect as the coffin passed. Charles asked “Please, sir, who are they going to bury?” The man replied: “My son, that is the body of a great poet, Edgar Allan Poe. You will learn about him some day.” Charles could have hardly dreamed that 60 years later, he would receive the “Poe Medal” at that very spot for authoring the poem that would pay tribute to Poe on his 100th birthday.

His route to art school took him past a hospital, where, one day, a plain coffin was being taken to a hearse nearby. Two gentlemen had their hats off, standing by with respect as the coffin passed. Charles asked “Please, sir, who are they going to bury?” The man replied: “My son, that is the body of a great poet, Edgar Allan Poe. You will learn about him some day.” Charles could have hardly dreamed that 60 years later, he would receive the “Poe Medal” at that very spot for authoring the poem that would pay tribute to Poe on his 100th birthday.

Not all of Charles’ interests were artistic. He also loved reading about the West and various wars. It was a great, exciting time for a young man when the nation was going to war against Mexico.

In addition to his studies, Charles’ life during his teens involved working as a clerk for several different businesses in Pittsburg, as well as Baltimore until he and his mother began traveling to Bavaria to visit her relatives. They experienced several horrific Atlantic Ocean crossings. When returning to the United States in his late teens, Charles worked menial jobs such as wood cutting, river boating, and more store clerking.

By 1851 at age 16, he found himself in Boonville, Missouri. Five years later as the disagreements between Kansas and Missouri seemed ready to boil into full-fledged war, seemingly Charles would have to be a part of it. He joined Missouri forces, drilling and training every night until they seemed ready, but the situations cooled enough that the unit was disbanded. The next three years Charles spent some time with his father in Iowa, then traveled in Europe again, returning to the United States and locating to New Orleans in 1859, where he spent a couple of years teaching school along the Mississippi River towns.

1861 was an eventful year for Hubner. In Fayetteville, Arkansas, he entered Confederate artillery service, meeting the love of his life, Ida, in that same place. Their romance was fast forming, but they were determined to not marry until peace prevailed, so the courtship would last four long years. Charles’ battery was in Company H of the first Tennessee Regiment, Bee’s Brigade. General Elliott Bee was fatally wounded during the first major action of the Civil War at Manassas, Virginia along the creek called Bull Run. Charles was in the honor guard, firing rifle salute over the grave of General Bee.

Charles spent his year’s enlistment fighting with the artillery and helping high command manage their armies with his acquired clerical skills. When his time was up, he left Richmond for Chattanooga and joined the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, where he achieved the rank of Major. He had charge of the headquarters couriers, detailed to carry military dispatches, and served in this capacity later under Joseph E. Johnston from Chattanooga to Atlanta. In fact, on July 17, 1864 at 10 p.m., Hubner was charged to deliver a telegram to General Johnston which relieved him of command of the Army of Tennessee, just two days before the Battle of Peachtree Creek.

After the fall of Atlanta, Charles was ordered to run the telegraph office in Selma, Alabama, a huge supply and shipping depot for the South. When the war ended, he was mustered out of service in Selma, where he obtained a position as a clerk in a book store. He began to write and contribute poems to the Weekly Visitor and the Selma Daily Times. In the meantime, General Johnston was writing his own history of the war. The two men were well acquainted, and Johnston sought a quiet and secluded desk in the rear of the book store to do his writing. The two former Confederate officers had numerous conversations regarding the war.

Finally on November 15, 1865, Charles and Ida were married at Woodbine, Tennessee. For three years the Hubners were very happy. Charles worked for several papers as editor, and their son was born in 1867. Later Charles contracted malaria and was so sick that doctors told him to go live in Europe to be treated there, so he left his wife and baby and went to his mother’s residence. By 1869 he recovered and returned to his wife and son, establishing himself in Memphis. It was there Western Union hired him to take charge of their Atlanta office. On January 1, 1870, the young family arrived in the city that was to adopt them.

In the next five years, the Hubner family grew by two daughters, while Charles became less and less a telegrapher and more and more a contributor and editor of newspapers and periodicals. They had a happy family and life was wonderful until tragedy struck. In 1875 Ida developed a fever and a distressing cough that persisted in spite of all the doctors could do. Four months later on January 29, 1876, Ida Ann Hubner died. She was buried a few days later in Oakland Cemetery.

Before she died, Ida begged her best friend and neighbor, Mary Frances Whitney, to help Charles look after the three children. In fact, it was the whole Whitney family that helped Charles. They took care of his children in the daytime, and after work Charles had his dinner and then picked up the already-fed kids and took them home. Before long, he was taking his evening meal with Mary Frances Whitney as well, and “Miss Frank” became a close friend to both Charles and the children.

The two would talk for hours about literature and music, and they visited Ida’s, grave. Charles and Mary Frances planted flowers all around the grave together. He needed her, and she loved him; it was inevitable that they would become man and wife. They married on March 15, 1877 and on February 23 of the next year, a son was born. Two years later a daughter was born but died as an infant.

During that time Charles’ career skyrocketed. He wrote for major publications and had several books published. His friends included Sydney Lanier, Joel Chandler Harris, and other men who topped the Southern literary field in those days. Charles’ days and many evenings were occupied with the sort of things he reveled in. His wife loved hearing about those things, and they had many happy times together.

Once a month Mrs. Hubner and her mother, Mrs. Joshua Whitney, loaded their buggy with tools, a lunch basket, and the children, and they’d drive out to Oakland Cemetery to work on the family plots. In about 1881 they planted a small magnolia tree on the Hubner lot, which has grown to impressive size today. The children played around the mausoleum nearby, admiring the angel who guarded the graves of their Aunt Julia and two little cousins.

The Hubners had a long and fruitful life together. Mary Frances lived until 1927, and she was buried on her family lot at Oakland Cemetery, alongside her mother, father, and others. In 1928 Charlotte’s Poetry Society of the South named the Major “Poet Laureate of the South.” In early 1929 Charles Hubner died at nearly 94 years old. There were very few Georgians that did not know Major Charles Hubner, either personally or by reputation. The magnolia planted by “Miss Frank” and her mother is a living memorial to the mother and daughter bond.