Take a Closer Look at the Foundation of Oakland: Bricks (Part 4)

By Ashley Shares, Director of Preservation

“Hood Brick is Good Brick,” the newspapers printed, in reference to the quality and geographic dispersion of B. Mifflin Hood’s ceramic products. But the words also had a deeper meaning, one that spoke to the fair labor practices the company applied, which stood in stark contrast to the convict labor used by James English and Chattahoochee Brick (covered in Part 3).

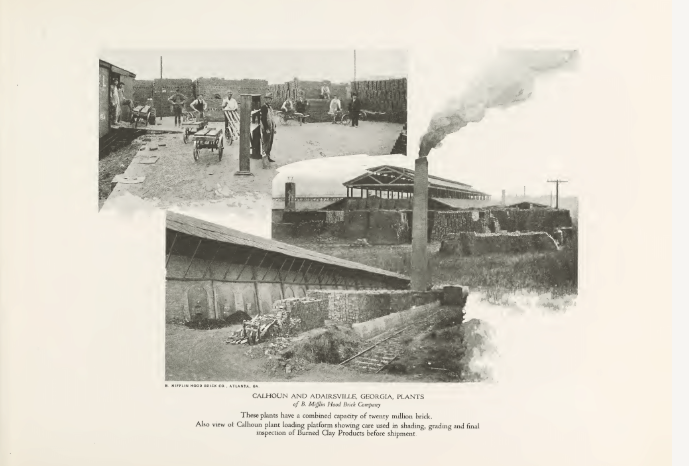

Instead of relying on outdated and barbaric tactics to quickly produce large quantities of bricks, Hood used innovative techniques and modern equipment to create bricks and tile. Benjamin Mifflin Hood was born in 1877 in Maryland. Although he studied theology at the University of Pennsylvania, he also fell in love with industrial technology after attending Atlanta’s Cotton States Exposition when he was eighteen years old. Hood came to Atlanta from Philadelphia in 1904 and worked in real estate, but soon switched careers and quickly made a name for himself in the brick industry. By 1910, he had six brick plants across the southeast: in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina, all pulling from local shale sources and using the newest technologies (including some he helped invent himself!) to make bricks, tile, pavers, and countless other structural and decorative ceramic products. His first showroom was in the Candler building. Later, in 1921, he purchased and expanded a large brick warehouse at 686 Greenwood Avenue in Virginia Highlands from the Austin Brothers Bridge Company, where the business thrived until Hood’s death in 1946.

Hood was shocked by James English’s convict leasing system and was an outspoken critic of the inhumane practice. He took out countless ads in the Atlanta Constitution denouncing the practice and promoting his own “shale brick made by skilled free labor out of nature’s best material.” He lobbied for convict leasing to be outlawed, not necessarily for moral reasons, but because it stifled progress and competition. He believed that convict labor should be used for state projects, namely, road construction. He proclaimed that the reasons Georgia’s roads were so poor were due to all the convicts making bricks rather than building roads.

Hood’s influence on the clay industry was immense, not only because of his help in ending the convict leasing system or because his bricks were used all over the country. Hood was hell bent on innovation and strove to help the South catch up with the industrialized North. Prior to World War I, he opened the first quarry floor tile company in the southeast. After the war, his was the sole shale roof tile operation in the region, providing much-needed products to the south without the need for shipping longer distances. He also created the new ceramics department at Georgia Tech in 1924 and was named president of the American Ceramics Society in 1927. During WWI, as well, Hood was approached by the US government and became part of a team that designed and manufactured ceramic spiral acid rings, which were used in explosives.

Upon his death, Mifflin Hood Brick Company was sold, and the proceeds were given to Georgia Tech University and St Philip’s Cathedral. Hood’s legacy lives on through the ceramics department at Georgia Tech, as well as the countless buildings his bricks and tiles are a part of, including Inman Hall at Agnes Scott College (1910), Grady Hospital (1912), and the roof of East Lake Golf Club (1915).